Are Cash Pools Scams?

January 23, 2018

Junior Lauren Margolis, like many others, found out about cash pools through social media, where some teenagers, including some Palmetto students, have been promoting the money-making plan in efforts to get others to join their groups.

“I knew people who had done it and it ended up working for them so I decided to try it,” Margolis said.

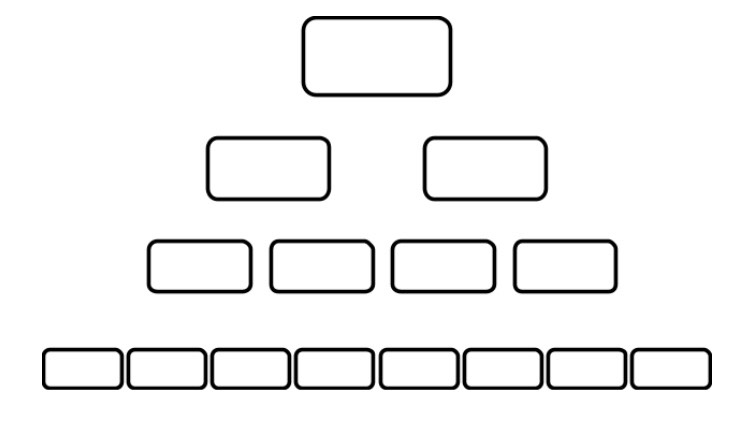

For those that have not seen cash pools before or do not understand how they work, here is a quick explanation:

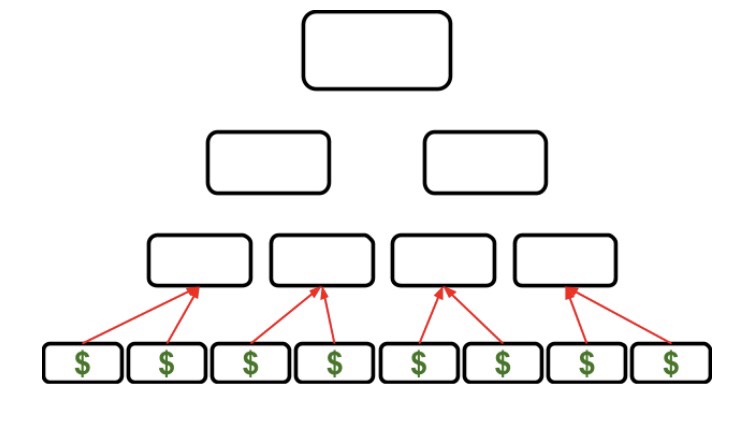

1. Each group has 4 rows with one spot at the top, two in the second row from the top, four in the third row from the top, and eight in the last row.

2. The people in the third row recruit two people each to fill up the eight spots in the fourth row. Recruits join the system by paying $100 each. (Red arrows point towards the recruiter from the recruit)

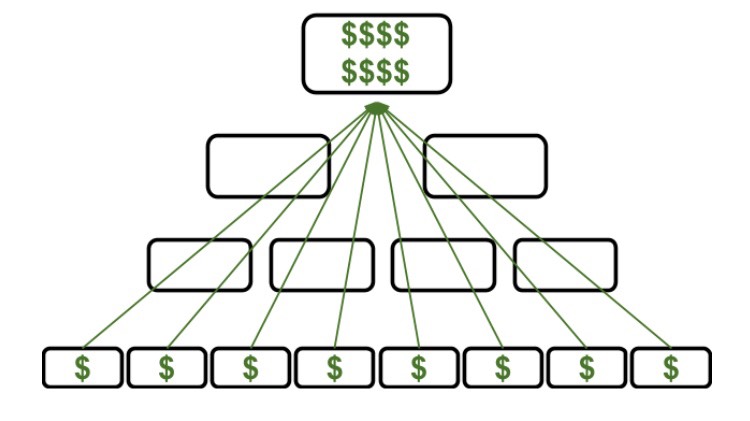

3. The total $800 dollars collected from the fourth row goes to the person in the top spot. Once they collect the $800, they leave the top spot. After they leave they can choose to rejoin the same or another group or refrain from rejoining and keep their $700 profit.

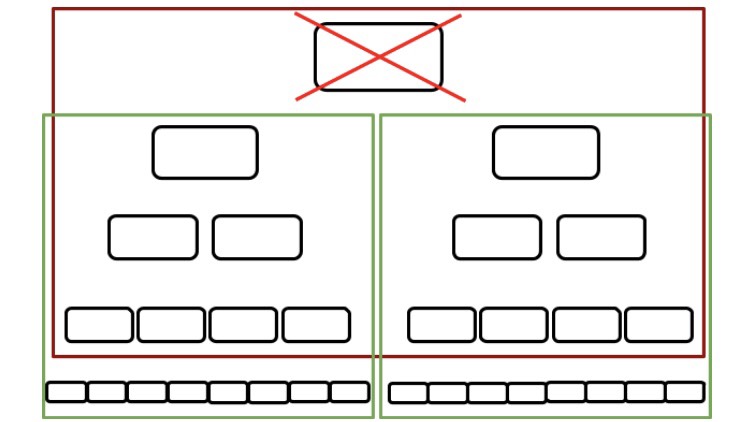

4. After the person in the top spot leaves, everyone in the rows below moves up a row. The people in the second row now each hold their own top spot. (Original group surrounded by red rectangle, new groups surrounded by green rectangles)

5. The cycle of payment and moving up through the ranks continues with everyone eventually moving into their own top spot, collecting $800 and leaving.

The shape and rules of the system could frighten some people and its promoters know that, as indicated by the frequently used phrase attached to these promotions: “this is not a pyramid scheme.” Margolis says that she too thought the plan sounded suspicious when she first heard about it.

“I didn’t see how you could give up fifty bucks and end up making 400,” Margolis said. “At first I was super sketched out.”

According to investopedia.com, a pyramid scheme involves a recruit paying their recruiter a fee as an investment to join a group. The recruit then makes a profit by recruiting more people into the scheme under them who in turn make profit by recruiting more people below them and so on.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, pyramid schemes are illegal in the U.S., and in many other countries, because they are destined to collapse because there is no infinite supply of people to recruit. Those that are left at the bottom of the scheme without people to recruit, which would be the vast majority of the people in the scheme, would lose their investment. In one of the most famous examples of a pyramid scheme, Bernard “Bernie” Madoff was arrested in 2008 for conducting a pyramid scheme and lost around $50 billion in investor funds.

However, cash pools differ in that the person at the top of the pyramid does not stay in that position and rather leaves once they have received their $800 from the bottom investors.

“It seems like money for nothing,” Advanced Placement Macroeconomics teacher Joel Soldinger said. “When that’s going on I’d be a little bit leery about that.”

While Soldinger could not confidently define the system as a pyramid scheme, he did say he did not think it was a safe investment and expressed concern about the system’s entirely recruitment-based business model.

“Potentially it could work, but if one person doesn’t pay the thing breaks down, people get angry and I think that’s where the problem starts to arise,” Soldinger said.

Oftentimes, those that promote these cash pools tell investors to recruit their friends and say the system is based on recruiting trustworthy people into the group. Senior Nicole Bonnemaison has thought about starting her own cash pool with her friends.

“I don’t want to join somebody else’s because I don’t want to get scammed,” Bonnemaison said. “But I know that if I started my own I wouldn’t scam anybody. I wouldn’t want to join [a group with] somebody who I don’t know. But if a friend of mine that I knew wasn’t going to scam me started one, I would definitely join it.”

Joining one with friends seems to be an ideal situation; oftentimes, participants join groups with strangers. But no matter who joins a group, recruits receive no guarantee that they will make a profit off their investment. Cash pools and pyramid schemes seem to share a similar problem: a dwindling supply of new recruits. While theoretically the supply of new recruits is infinite under the cash pool system, those that leave a group show a reluctance to join again. While Margolis saw profits from her first cash pool, her second group did not fare as well.

“All my friends that did it didn’t feel like doing it again so nobody really started joining,” Margolis said.

Despite the failure, Margolis says she doesn’t think she was scammed and recommends that if other people are interested they should try it.

“It’s not a scam. If you get people to join you’ll make the money,” Margolis said. “I don’t think I was scammed. I think it just didn’t end up working. I know it can work I just think it happened not to.”

Although many have seen profits as a result of cash pools, from an investment standpoint it is still fairly risky.

“It sounds good and it sounds like a way to make some money quickly,” Soldinger said. “But it’s not something that I would recommend or run out and say ‘go do this.’”