Concussions: Behind the Facemask

January 19, 2016

On Sunday afternoons Americans cluster around pubs, living room television sets and tailgates as the first football games of the day kick off. The day before, college students make last-minute stops for lunch before piling on a bus to the stadium to see the boys of fall compete against long-time rivals. In a culture obsessed with the sound of colliding pads and forceful tackles, the inevitable consequences of repeated brain damage are often overlooked for the love of the game.

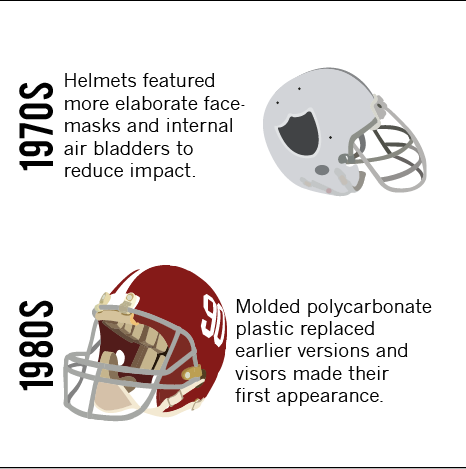

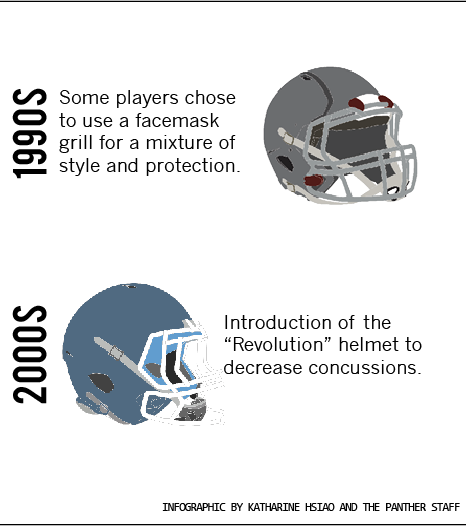

Trauma through the Ages

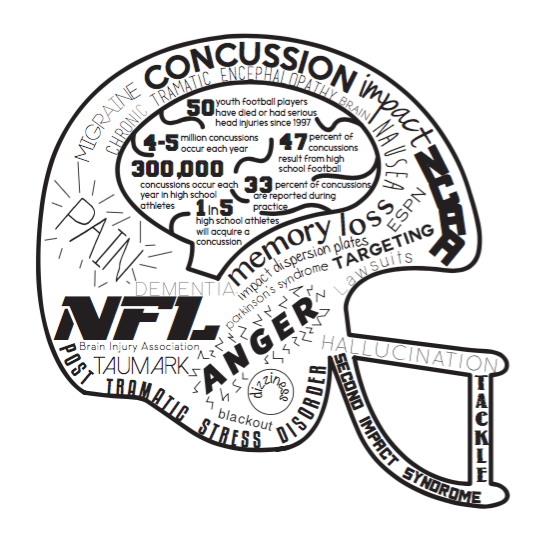

Concussion: a word defined as a traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by a violent blow to the head, jostling the brain against the skull and creating chemical imbalances. A concussion diagnosis relies on a scale from one to three, Grade 1 representing the least intense form and Grade 3 representing the most severe. Regardless of concussion intensity, repeated blows to the head create a cumulative TBI history, further damaging the brain with each shock.

Concussion prevention applies to all ages and ranks of athletes, however protection is most vital for children, when the development of the human brain peaks. From 2010 to 2012, Pop Warner youth participation dropped 9.5 percent – a distinct decline compared to the league’s previous popularity. Youth athletic participation decreases as parents learn more about the effects of traumatic brain injuries and its implications for their children’s future.

“I think the younger kids are the ones who need to be [taught], because the quicker they learn, the easier it becomes for us on this level to teach them,” head coach Mike Manasco said.

According to Head Case, an organization dedicated to raising awareness and protection for athletic brain injuries in youth, cumulative concussions raise the risks of permanent neurologic disability to 39 percent.

At the high school level, competition takes a sharp incline, as does the risk of concussions. Overwhelming amounts of procedures and precautions suggested by medical professionals ensure the maximum amount of concussion prevention possible.

Some high school athletes refuse to notify parents, medical advisers or athletic trainers of a potential concussion out of fear of missing practice and games.

“This is frightening to me since playing with a concussion is more serious than the concussion itself,” Athletic Trainer, Michelle Benz said. “When the brain is shaken, it reacts like a soda bottle being shaken. Chemicals react and move in and out of the cell and create a foam, or fizziness. This reaction creates a vulnerable position for the brain. If it is hit again during this time of chaos, it has the potential to react the same way a shaken soda would if it were hit hard….it will explode.”

Data compiled during the last ten years reveals that out of 14 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) sports, football has the highest concussion rate at 37 percent followed by women’s soccer at 12 percent, women’s basketball at nine percent and women’s field and ice hockey at two percent – the lowest concussion rate.

It has not yet been proven that gender plays a role in concussion risks, but data offers the assumption that females are more susceptible to concussions.

“Studies have shown that females are at higher risk for concussions over their male counterparts, however the reasoning has been suggested that it may be to the more honest reporting of females,” Benz said. “Other factors have been attributed to neck and body musculature, which absorbs more force and keeps the head more stable.”

Palmetto originally led Miami-Dade County’s efforts towards safer prevention methods for concussions in high school. After the 2004 Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport, a guideline on how to react to athletic concussions, Palmetto decided to use neurocognitive baseline testing utilizing computers for concussion detection; it was not until three years later that any other school in the county followed suit. Palmetto athletics now also uses Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT) testing for each player, a paper-based assessment for athletes to evaluate their symptoms, rather than verbal assessments after receiving a concussion.

“Each athlete now has to view a Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) video that explains the signs and symptoms of concussions and how to know when to speak up and report these signs,” Benz said.

A medical assistant or athletic trainer attends every sporting event at Palmetto, including football, basketball, volleyball, soccer, wrestling, baseball, softball, track and lacrosse games. Lifeguards monitor the athletes at swimming and water polo events.

Senior Alec Rodriguez, a slot receiver for the varsity football team, has a nonexistent concussion history and feels safe playing knowing that medical attention is available in the aftermath of an injury.

“Michelle [Benz] does a good job at diagnosing concussions and treating concussions, so usually our players don’t play with concussions, but it’s a matter of having a good trainer with good experience who knows what they are doing,” Rodriguez said.

Palmetto tracks its concussion history, along with all other MDCPS high schools, by sending a reporting form to the concussion clinic at the University of Miami.

“Data specialists organize the data and provide year-end statistics to each school in regards to the number of concussions via gender and sport,” Benz said.

Similar conditions generally persist from the high school to the college athletic environment, including limited sideline medical staffs and lackadaisical coaches who may value a win over the health of a player. Recent technologies and advancements in playing gear have helped reduce these risks as researchers pursue more preventative measures. Some coaches opt to send players back in the game after a hit for the team’s sake.

“It’s kind of selfish because they’re only caring about that season whereas they should care about the player’s health,” sophomore Federico Zalcberg said.

Professional athletic gear provides the most protection for its competitors, although certain sports maintain high risks of injury. The most amount of professional concussions occur in the NFL.

In 2002, Dr. Bennet Omalu, Nigerian forensic neuropathologist and founder of TauMark (a company aimed toward the prevention of concussions in football) discovered Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) after performing an autopsy on Mike Webster, one of the most well-known centers in the history of the NFL. Webster played for the Pittsburgh Steelers and Kansas City Chiefs from 1974 to 1990, suffering an excessive number of untreated concussions over the years, leading to his tragic death. A recent lawsuit against the NFL now provides retired football players with endorsements for brain damage. Football players were never informed of its risks. The NFL faced a period of denial.

Hitting Home

Behind the pep rallies, behind the hype of the game and behind the psyche of the athlete resides a brain vulnerable to excessive impact. While professional athletes have ample time and medical assistance to monitor their health, Palmetto athletes often manage to juggle schoolwork, a social life and an athletic schedule. Intervening concussions can make it all the more difficult.

Sophomore and softball player Seattle Thompson experienced the effects of a concussion when she was hit in the face with a softball while running from third base to home plate. She believed she was fine until she began to throw up.

“It makes you really dizzy,” Thompson said. “They checked my eyes and I had to sit down for the rest of the game.”

Thompson’s coaching staff and doctors prohibited her from playing again until officially cleared.

“The hardest part was not being able to get back in the game, and then we lost,” Thompson said. “If it’s my rivals, I value the game more [than my health].”

Concussions are not limited to athletic injuries. Senior Edward Smigla plays water polo for Palmetto and sports a mere speedo cap during games, providing minimal protection due to the slim risks of head-on contact. Outside of water polo, Smigla received a mild concussion in December due to a bicycle accident. His doctors cleared him to play two weeks after the incident, but Smigla suffered the effects of a concussion regardless.

“I was nauseous – the only time I wasn’t nauseous was when I ate,” Smigla said. “I also had headaches that would come and go, and I couldn’t stare at computer screens for a long time.”

In case of a sports-related concussion, Smigla knows his coaches and trainers will take extensive measures to treat it.

“I try not to get hit in the head [in water polo] so I don’t get a concussion because that means I’m out more, and I don’t want to be missing practice,” Smigla said. “If you get hit in the head, they pull you out right away and ask you if you’re okay. A couple times I’ve seen them call a person over and make sure they know their name, where they are, what’s going on and what just happened.”

Bring Your A-Game without the Pain

New technologies and playing techniques can help athletes stay safe throughout practices and games. Players who re-enter a game after receiving a questionable hit to the head – concussion or not – put themselves at higher risk of receiving more intense damage, known as Second Impact Syndrome. Nothing exists to guarantee concussion prevention, but high school athletes can increase self-awareness about how to keep themselves as safe as possible.

“It is imperative that football players never lead with their head while tackling or drop their head down as they head into a tackle,” Benz said. “In soccer, snapping the neck while going up to head a ball reduces the rotational forces as well as the risk of hitting an opposing player’s head. Strengthening of the neck musculature has also been shown to reduce the translation of the head during contact sports.”

Awareness of how to handle concussions at the high school level may help reduce the rates of traumatic brain injuries.

“If the student athlete receives a blow to the head, he or she should perform a quick self-evaluation of their mental and physical capabilities and deficits,” Benz said. “If he or she develops a headache, or becomes dizzy, nauseated, off balanced, has memory issues, develops unusual fatigue or lethargy they should stop play immediately and report to their athletic trainer, parent or coach for further medical evaluation.”

New types of gear frequently appear in stores for better protection; keeping an eye out for them, with the approval of the team and coach, can help protect the brain during gameplay.

A Changing Sport

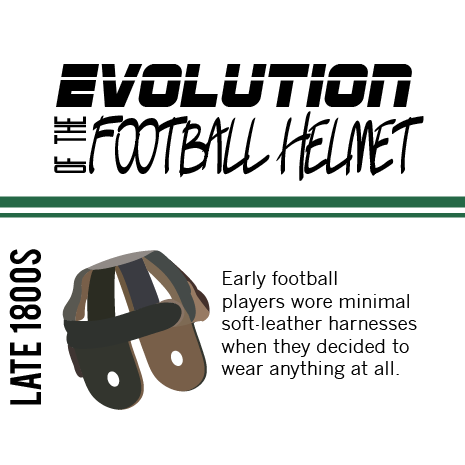

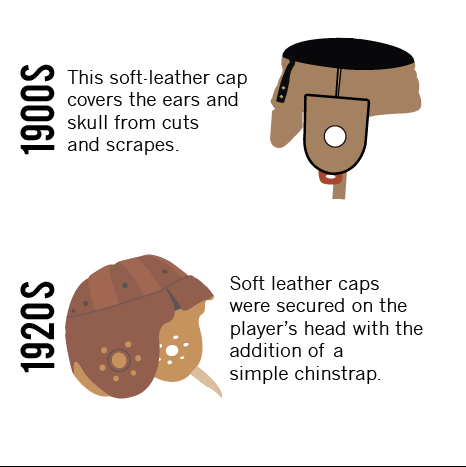

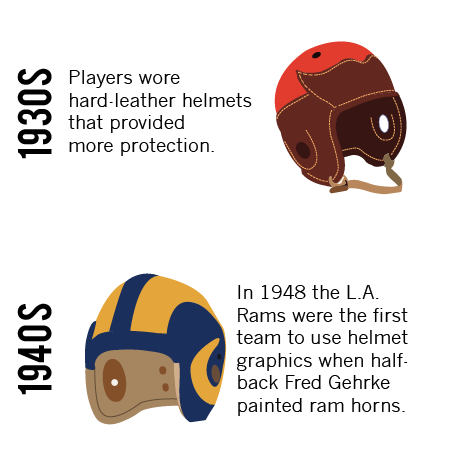

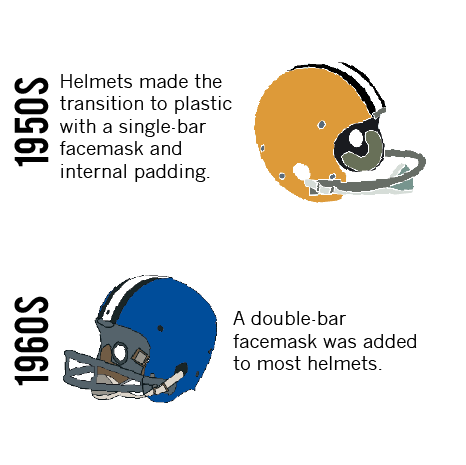

Perhaps the most revolutionized sport of today is football, with its extensive research committees and evolving gear to help improve player protection after the alarming CTE discoveries. Since football’s origins in America in the late 19th century, players have competed aggressively and head-butts have occurred repeatedly due to the rigorous competition.

Players wore nothing at all to protect the skull in its earliest days, much like rugby players. Even with better protection than their rugby cousins, football players possess high risks of concussions and CTE merely due to the tackling style they have learned and executed for over a century.

Rugby players tackle opponents by engaging the entire body, wrapping their arms around the opponent’s torso and using the force from their shoulders to bring the man down. Football players tackle opponents head-on. Palmetto football Head Coach Mike Manasco and Assistant Coach Bobby Vernon promote the proper tackling techniques among high school football players.

“I think a big part of it is teaching youth not to put the emphasis on the head, wrapping [opponents] with the body, more like a rugby-style tackle,” Rodriguez said.

New regulations in the NCAA and NFL enforce this philosophy. The targeting penalty – frustrating to the football universe for its current state of ambiguity – ejects the guilty player if he hits an opponent with the crown of his head. A player must stay out of the game for one play if his helmet falls off during the preceding play. Multiple calls since its official appearance have been debated as either fair or over-precautionary.

“I believe we’ve got to keep the head out of the game,” Manasco said. “It’s a good rule, I just think there needs to be more clarity on what it is and what it isn’t.”

The evolution of the football helmet serves as a contributor to player safety. New prototypes, unlike the leather caps seen in the early 20th century, feature a variety of assets to help reduce the impact of a hit, including special air-filled interior padding, cooling gel packs to lessen damage, sensors to alert sideline staff of a possible concussion and impact dispersion plates. The latter makes the helmet appear to have multiple sections and disperses the impact of a hit around the entire skull.

Facemasks, chinstraps and mouthguards contribute to concussion prevention as well. The jaw plays a decisive role in the occurrence of a concussion. A blow from below the jaw causes concussions equally as dangerous as hits from above.

Concussion

This past Christmas, the movie Concussion starring Will Smith brought audiences a new dramatic look at CTE, the disease that plagues hundreds of ex-professional football players. Following the struggle of the aforementioned Dr. Bennet Omalu to raise awareness about this disease in a country that denies its most popular sport as detrimental, the film takes audiences on an emotional and scientific journey surrounding what has become the biggest obstacle to America’s pigskin pastime.

Read a review on the movie – without pesty spoilers – to help decide if you will take a trip to theaters.